ARCHISCENE Magazine editor Katarina Djoric sits down with Junichiro Yokota of Junichiro Yokota Studio to discuss Lights with a Story, the designer’s poetic presentation for Salone Satellite. Known for a process that begins with concept, material, or use, depending on what speaks first, Yokota builds each object through a matrix of values. His works draw meaning from compassion, precision, and quiet experimentation, using materials like washi paper and recycled optical glass to shape emotion into form.

Key pieces like Toi and Kaleido express this sensitivity. Toi, crafted from delicate Japanese paper, invites interaction through its adjustable height and soft presence, while Kaleido uses repurposed glass to create naturally unpredictable patterns. Sustainability runs through the practice, not as a visual choice, but as a response to industrial waste and overlooked materials. Yokota’s lighting does more than illuminate; it becomes a gesture of empathy, designed to support conversation, stillness, and human connection.

Each of your lighting pieces tells a story. How do you begin shaping that narrative when designing a new object?

There are several important elements when designing: the “thought/message,” the “material,” the “usage,” and the “tailoring.” The design becomes complete by combining these elements. (“Thought/message” could also be called the concept.)

I believe each of these elements should have its own story. The more meaningful the components are when combined, the more convincing the result becomes. However, the process remains very flexible. Sometimes the design begins from the “thought/message,” and sometimes from the “material.”

Toi feels both poetic and personal, with its adjustable height reflecting the idea of “your” light. What inspired this relationship between light and the user?

The idea is rooted in “kindness and compassion.” Most lighting in the world is beautiful and dynamic, designed to illuminate entire spaces. However, we tried a different approach, which resulted from ongoing trial and error.

Toi is made from a delicate and soft material, Japanese paper, and tailored for gentle light intensity. We wanted both the “thought/message” and the “usage” to be gentle as well. You can feel “thoughtfulness” through this lighting, as if someone were holding a door open for you. It might sound a bit abstract, but wouldn’t it be nice to have such gentle lighting in the world?

You’ve used washi paper in a way that both respects its history and pushes its form. What challenges did you face evolving such a traditional material?

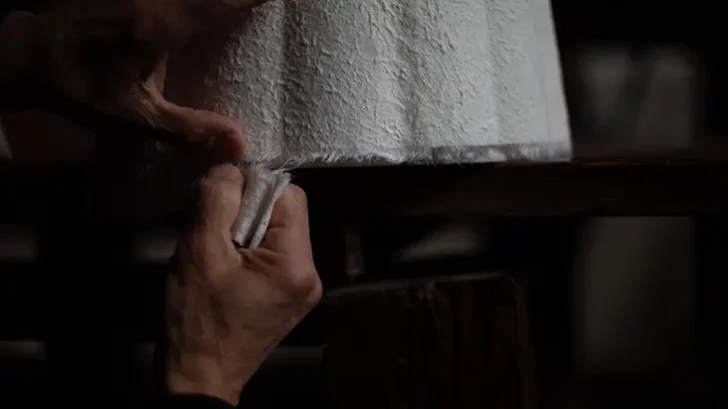

It’s estimated that more than 1,500 years have passed since the original form of washi came to Japan and evolved. Historically, it was used mainly for writing, and there was no method to form three-dimensional shapes using just the paper. (There were techniques like stretching paper over a structure, such as in chochin, but not forming with only paper.) Because of this, there are almost no craftsmen in Japan today who can mold paper into shapes. Finding someone was the first challenge.

Even after production started, we had to balance texture, strength, and light transmission to maintain the shape using only paper. Finding that balance was the most difficult part, especially at a size we had never attempted. We failed many times. Sometimes the shape wouldn’t hold and crumbled. Other times the paper was too thick and blocked the light, or it became too strong and lost the soft texture of Japanese paper.

Kaleido’s use of recycled optical glass results in one-of-a-kind patterns. How important is unpredictability and uniqueness in your design process?

Unpredictability and uniqueness might seem risky in design, because things you cannot control can cause the whole design to fail. But at the same time, I think the unexpected can be very fascinating. People are naturally drawn to gems or stones made by nature, not just glass. I think the patterns in Kaleido are similar to that.

If I remove the unpredictability and uniqueness from Kaleido’s patterns, it would become just an ordinary product. I want to express these qualities, even if there is risk involved. That’s how important it is to me.

What led you to explore sustainability through materials like washi and recycled glass, and how do you balance that with visual expression?

It started when I realized how many items, perfectly fine in my opinion, were being thrown away during mass production because they didn’t meet overly strict standards.

I also learned that conventions and industry standards exist for every material, and even usable items are rejected. For example, in the timber industry, wood with knots is considered defective. But for me, and for some users, that’s not a problem at all.

These items are thrown away because of convention and efficiency. I thought: if design can give new value to something with a knot or flaw, then it can contribute to sustainability. That idea motivated me.

Condivi is designed to encourage communication. Do you see lighting as a social tool as much as a functional one?

Yes, exactly. We want it to function as a social tool. There are already many functional, convenient, and high-impact designs in the world. But in today’s digital and internet-based society, we think it would be beautiful to have a shared light experience with someone standing next to you. Even just a small conversation could be meaningful. We want to create moments that allow for that.

You work across materials – paper, glass, metal. How do you decide which material best fits the story you want to tell?

I choose materials that don’t interfere with the story and help express it naturally. If I have a clear idea of what I want to say, the material often reveals itself. Of course, sometimes, like with Kaleido, the story is born from the material itself.

I want to continue using various materials and help people rediscover their value and new possibilities. That’s why I actively research different materials every day.

All three works reflect a sensitivity to both function and emotion. How do you ensure your objects remain technically refined while emotionally resonant?

My experience working on mass-produced items may have helped shape my understanding of function and technical aspects. But for me, the emotional part is most important. The works I exhibited this time all carry a message of “kindness and compassion,” toward people, the environment, materials, and traditional techniques.

We created many ideas and also abandoned many prototypes. This project reminded me that the most important thing is to keep going with heart. If you do that, you’ll always find people who understand and support the technical side.

How does exhibiting at Salone Satellite shape your dialogue with international audiences and future collaborators?

People from around the world responded very clearly, and the experience felt truly meaningful. Today, we can share our work not only by email but also through social networks. Once someone knows about you, it becomes easier to connect across distances. Salone Satellite gave me the opportunity to make those connections.

What is next for you?

The answer is very simple: I would really like to collaborate with European lighting and furniture manufacturers to present new work.

This exhibition received more attention than I expected, and I want to make the most of that opportunity. I’ll keep working hard to make it happen. I also plan to return to Europe soon, because important details are easier to discuss face-to-face. Another goal is to participate in next year’s Satellite. This time I only showed lighting, but next time I want to present different types of items.

I look forward to seeing everyone again in a year.

wow what a beautiful conversation! thank you for introducing us to Yokota’s work!