Han Gao approaches architecture as a way of thinking about systems, perception, and the invisible forces shaping contemporary life. From data centers to large-scale innovation campuses, her work transforms technological infrastructure into spatial experience, balancing analytical rigor with atmospheric sensitivity. In our exclusive interview Han reflects on rethinking architectural typologies, revealing hidden operational logics, and defining a design approach attuned to the conditions of the digital age.

In Data Drop, digital infrastructure becomes the primary spatial gesture. At what point did you decide the servers should move from hidden necessity to architectural protagonist?

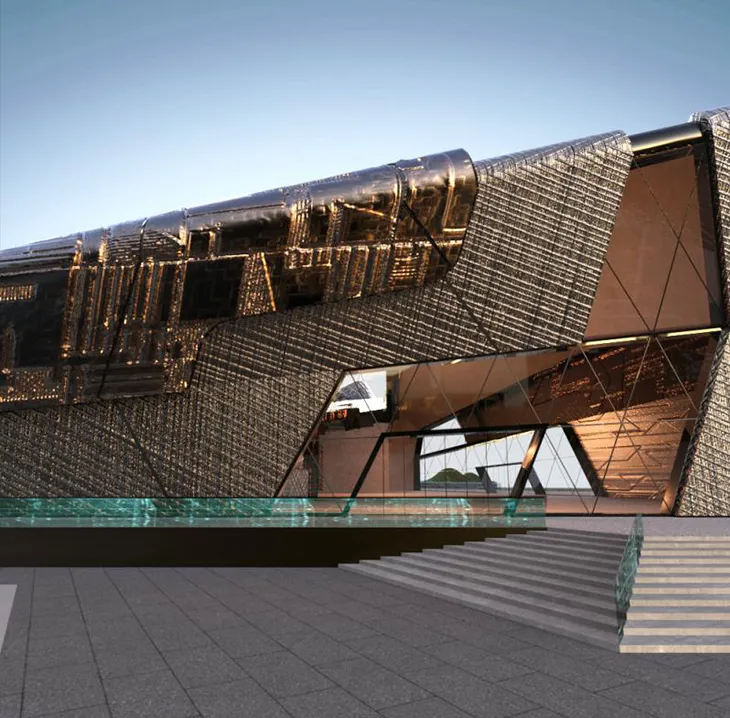

Very early in the conceptual phase, I realized that hiding the technological core of a data center no longer reflected how deeply digital systems shape contemporary life. Instead of concealing the servers, I wanted to transform them into an architectural protagonist – both symbolically and spatially. This decision became a key driver of the project and was later recognized by several international juries, including the NY Architectural Design Awards and TITAN Property Awards, which affirmed the relevance of rethinking infrastructure as a public experience. Making the servers visible was not only a design choice but a belief that architecture should reveal, rather than obscure, the systems that define our time.

The suspended data cloud introduces light, reflection, and temporal change. How did you choreograph atmosphere around an object defined by pure function?

The servers themselves carry no aesthetic agenda, but the light they emit, the heat they release, and the rhythm of their activity have inherent atmospheric qualities. My strategy was not to decorate them but to amplify their native presence through architectural tools. LED pulses become dynamic ambient light; a reflective ceiling softens and redistributes illumination; Slightly reflective dark metals capture shifting tones throughout the day.

The goal was to create a sense that the technology is “breathing.” The atmosphere emerges not from cosmetic effects but from the building’s sensitive response to the server’s real-time operations. Function becomes more experienced.

The diagrid system removes columns and produces a fully open interior. Was structural clarity a prerequisite for the conceptual clarity of the project, or did one evolve from the other?

They evolved together. Once the servers became the conceptual core, the structure had to support an unobstructed field that allowed them to command the space. The diagrid system offered both technical efficiency and conceptual purity. My work in large-scale U.S. commercial and research environments has reinforced a belief that structure and concept must operate in unison – clarity in one reinforces clarity in the other.

DESIGN

Cooling strategies linked to the river operate simultaneously as environmental systems and spatial narrative. How important is it for performance-driven architecture to remain perceptible to the user?

I believe performance should not operate exclusively behind the scenes. When environmental systems become legible, they deepen spatial experience and cultivate awareness of how architecture functions.

In Data Drop, the cooling system was intentionally revealed: Water flow aligns with circulation; Temperature gradients become sensory cues; Sound and humidity introduce subtle atmospheric layers

When public understands that these conditions originate from real operational needs – not decorative choices – the space gains transparency and educational value. Making performance perceptible allows infrastructure to become part of collective understanding rather than a hidden technical artifact.

Data centers are typically designed for control and isolation. What architectural tools did you use to counter that logic and introduce a sense of openness and spatial generosity?

I employed three primary strategies: the first is Inverting the typology. Moving servers from sealed rooms into a public hall reframes them as accessible spatial elements. I also dissolve boundaries. A continuous ceiling, open floor plan, and absence of columns create a fluid and uninterrupted interior. Then use light as a medium of openness. Natural light enters through the façade and interacts with the artificial glow of the servers, reducing the oppressive atmosphere typical of technical buildings. The result is a counterintuitive environment – one that is technically robust yet visually and spatially open.

The Autowell R&D Center shifts scale and program but retains a strong systemic logic. How do you approach designing coherence across research, manufacturing, and social space without flattening their differences?

My approach begins by identifying the “driving logic” of each program: Research means process efficiency; Manufacturing means structural rhythm and equipment geometry; Social space means patterns of gathering and movement.

Each space operates on its own logic, yet all of them can be integrated into a larger systemic framework. Coherence emerges at the system’s level, while differences are preserved through their distinct operational and spatial behaviors.

Photovoltaic geometry informs circulation and spatial sequencing at Autowell. How do you abstract technological forms into architecture while avoiding visual literalism?

My rule is simple: Abstract the logic, not the shape.

Photovoltaic systems are defined by two principles: Orientation and angle (optimization of light); Modularity (repetition and arrays)

These principles were translated into architectural elements: Angles which means directional paths and spatial openings, and Modularity which means rhythms in façade articulation and ceiling grids.

The result captures the essence of photovoltaic logic without mimicking its literal form. Users feel an order shaped by light and energy, not a superficial representation of solar panels.

Color plays a precise role in defining identity at Autowell. How do you think about chromatic restraint as an architectural tool in high-performance workplaces?

In high-performance environments, color must serve as information, not decoration.

My philosophy is that color should: Clarify functional zones; Support focus and reduce cognitive noise; Reinforce spatial hierarchy.

Restraint does not mean absence; it means precision. At Autowell, each color application carries directional, psychological, or organizational intent. The palette becomes a system that supports performance rather than visual embellishment.

Both projects reveal complex systems without aestheticizing them. How do you draw the line between exposure and excess when architecture engages with technology?

The key is to recognize the narrative potential of the system itself.

If the system is inherently powerful, it does not need embellishment. My role is to provide calibrated visibility for public to understand how things work. Also avoid emotional or stylistic additions.

The goal is to express the logic, not stylize the machinery. Once the expression becomes performative rather than truthful, it crosses into excess – something I intentionally avoid.

As digital and industrial infrastructures increasingly shape contemporary space, what do you see as architecture’s role in translating invisible systems into lived, intelligible environments?

Architecture today must act as a mediator between highly complex, often invisible systems and human experience. As digital networks, energy systems, and industrial operations become fundamental to contemporary life, the role of architecture is not simply to house these systems but to translate them into environments that people can understand, navigate, and emotionally connect with.

In my work, I focus on making these hidden infrastructures legible – turning abstract operations into spatial logic, material expression, and perceptible atmosphere. This approach is central to projects like Data Drop, where the building reveals – not hides – the technological forces shaping our world. The fact that this project has been recognized internationally through awards such as the NY Architectural Design Awards and the TITAN Property Awards reinforces for me that this way of thinking resonates beyond individual projects. It affirms that translating invisible systems into meaningful spatial experiences is not only a design challenge but a globally relevant architectural agenda.

Ultimately, I believe architecture must bridge the gap between the system and the human – making the workings of our digital and industrial era not just functional, but culturally and experientially accessible.